I really enjoy field work, and if I did not have the opportunity to spend at least part of the year working outdoors I do not think I would have stayed in Science. Field work almost always involves a team of people, for reasons including safety (working alone is verboten by most institutions and organizations, public and private), effectiveness and efficiency, and the realities of funding. Employing* undergraduate students as field assistants for graduate students, post-docs, professors, and other academic researchers has a long history, and each and every time this involves building a field crew, a team of workers to conduct the research, usually for the first time for at least some of the people.

* The

debate regarding unpaid positions for undergraduate students in labs and field

crews is one for another post; suffice to say I am extremely wary of unpaid

work, especially when a commitment of several months is required. This gets to

the heart of several issues in the modern practice of science, and there are no

clear and easy solutions to the problems of getting the work done with very

limited resources.

In my

experience, a professor makes most of the decisions regarding the composition

and schedule of a field crew for each field season. New graduate students are

recruited along with a few undergraduate assistants based on the funding

available and the sometimes-tentative research plans. I have never had any

direct input into the composition of the field crews I have been a part of

during my PhD and post-doc field seasons, though I can think of a few occasions

when I have been offered a hard veto that I have never exercised. I’ve never

had a major problem with any person I’ve been working with under field

conditions, and so far at least I have been able to smooth over or safely

ignore any minor issues that arise.

This topic

unavoidably addresses issues regarding women in science, a huge and very

important topic that certain parts of the blogosphere – at least, parts of the

bits I read on a semi-regular basis – talk extensively about. Most of those

discussions are from perspectives quite different from my own, though our

opinions may align well. In short, I support anybody having a career in science, because I’m having a great time

here and I think lots of other people would, too. There are of course much more

important reasons to support greater equality in science and in other areas,

and I like those reasons, too.

Field work

often includes activities in which a person’s physical strength is an important

factor. Field crews I have been a part of have ranged from mostly-male (Arctic

2010 – 3 out of 4) to mostly-female (this summer, 3 out of 4 for most of the

time). I am the only male in the lab group I am a part of for this post-doc,

and nearly everyone in this lab does at least some field work.

Over the

last few days, and for the next week, I have been working with one other

person, Marie-Claire, a scientist from Universite Laval. She helped me with the

last of my 2015 summer field work, and I have been helping her with some of her

work. She pointed me towards a paper (Newbery, 2003) she read some time ago

that I managed to find during one of our rare encounters with a useable

internet signal a few days ago.

Newbery, L., Will Any/Body Carry That Canoe?

A Geography of the Body, Ability, and Gender. Canadian

Journal of Environmental Education, 2003. 8: p. 204-216.

This is a

paper rather outside my usual academic reading, though not outside of topic

areas I spend much of my time thinking about and talking about. To (awkwardly,

and probably poorly) summarize, Newbery presents arguments regarding the

concept of “strong enough” or “capable of performing that task” that could, and

in most cases should be used as indicators of the suitability for a given

person for a given role or job.

Among the

various things we (“my” field crew) did this summer was boardwalk construction.

Working in a wetland means building places to walk to limit damage to the

vegetation; one of my colleagues quoted his former graduate advisor: “The

boards are to protect the plants, not to keep your feet dry!”. The minimum

boardwalk is literally just a board, something like an 8-feet-long 2x8 thrown

down on the wetland in the direction one might wish to walk. I find this

unacceptably primitive, and prefer something that doesn’t slide away or lever

up and swing sideways when I step on it. Not just to keep my feet dry – I’m

wearing big rubber boots, my feet stay dry regardless – but to prevent

accidents and to prevent a big piece of wood smashing into various bits of

scientific equipment. More acceptable designs include cross-pieces, a bit of

2x4 or 6x6 the walking surface is attached to with nails or screws that helps

to keep the boardwalk in place. In extremely wet areas, where we are

essentially working in a broad, shallow pond with a substrate made of very soft

and water-saturated partially-decomposed organic matter, upright posts are used

to minimize the pumping of the spongy ground that results from a person walking

on the board. We measure gas flux, among other parameters, and pumping the

ground leads to outgassing that invalidates our measurements of “typical” gas

movements. The uprights I have installed this summer are 2x4s cut with a

diagonal end and driven down into the peat.

Sometimes,

an upright can be simply pushed down into the peat, then horizontal boards

attached to it. Most of the time, however, an upright must be hammered down. A

one-handed mallet, such as the 3-pound rubber mallet I purchased a week ago,

works in moderately soft peat but is fairly exhausting where plant roots or

other obstacles interfere with the post-driving. A two-handed hammer, such as an

8-pound sledge or a similar-weight deadblow hammer, is the best way I have seen

to efficiently drive large stakes or posts into the ground. However, while I am

(barely) strong enough to wield such a hammer in the usual manner – swing up

over my shoulder, power stroke with the hammer nearly vertical above my head,

driving down with the bigger muscles of my abdomen as well as my arms and

shoulders – many of the people I work with are not able to swing such a hammer

in that way. Instead, they lift the head to just above their head, with the

handle nearly horizontal, then drive downwards using only the muscles of the

arms. Power correlates very clearly with the speed with which a stake can be

driven to the desired depth, so in some situations I am about twice (or even

more) as fast as my colleagues. Accuracy is obviously important in this task, a

missed stroke might be merely annoying or it could cause a serious injury. So

it is important that one only uses this tool in a way that does not overstretch

their strength or skills.

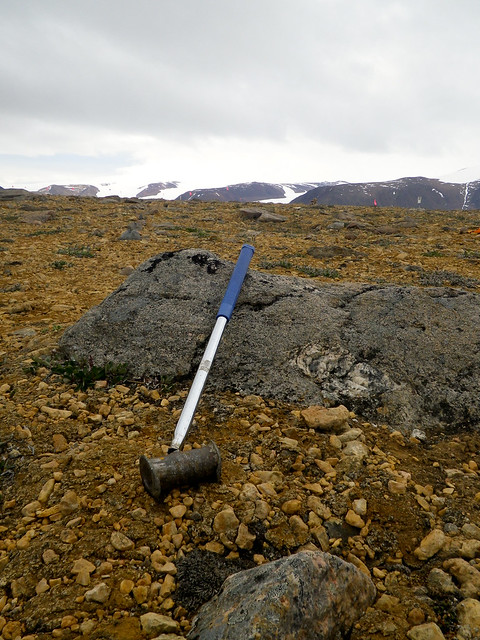

(Picture

unrelated) If you pound enough with a big dumb hammer, eventually it breaks.

Doesn’t matter who does the pounding, hammers have a set quota of bangs they

can handle before they catastrophically fail. This 8-pound deadblow hammer came from Princess Auto with a layer of hard blue plastic wrapped around the metal head. That chipped off over a few days of pounding.

Speed is

probably the least important factor in this task, despite the automatic desire

by anybody picking up a stake or hammer to just blast it out as quickly as

possible. Newbery (2003) speaks of this subconscious urge and spends some time

discussing difficult physical feats and the pride associated with success,

measured perhaps by an ability to complete a task without interruption, or on

the first try. It is rapidly apparent on some reflection that reaching the goal

– boardwalks built to avoid outgassing, canoe and gear transported from one

lake to another – is the only factor that matters (with the unspoken but

important addition that safety – no injuries – comes first [or second or third, if

you’re Mike Rowe]). Keeping the goal in mind, as well as the bigger

picture of both safety and daily, weekly, or monthly work goals, certainly

helps with safety because there is less pressure to rush through difficult

tasks, and makes my life much easier because the attitude towards the work

relaxes, for everyone.

This gets

back to the “strong enough” or the simple binary “capable / not capable” that

Newbery (2003) describes. I can carry two boards over my shoulder; my coworker

might be able to carry only one, cradled in her arms horizontally in front of

her, and she walks more slowly too. No matter, the boardwalk will still go to

where we need it, the work will still get

done, and if I try to do it all myself I’ll burn out or get injured, in

addition to the damaging effects on team morale if I pull some sort of

manly-man silliness.

Newbery

(2003) also briefly discusses the emotional reactions to achievement – if you

think you might be able to do

something, then you do it successfully, it feels pretty good, to over-condense

what looks like a rather sophisticated argument built on philosophy I’ve not

yet encountered. Aside: I think I understood around half of Newbery (2003), the

other half relied on an understanding of current philosophical work that I just

don’t have. Getting back to achievement, I think letting people try, and either

succeed or fail (and hopefully try again!) is far superior to any attempt to

shield someone from something I might suppose they are not capable of doing.

There is almost always more than one way to complete a given task* and I lack

the imagination to instantly think of every possible method.

* Except

the proverbial skinning of a (dead) cat – “There’s more than one way to skin a

cat!” is an ironic statement because really, the only way is to get a firm grip

and pull. That’s something I learned in a 3rd-year Biology lab,

during the requisite cat dissection. We had named the dogfish “Byf” but I

cannot recall the name we gave our preserved tabby.

This

long-ish, meandering post is meant as the beginning of a conversation, or just

a point somewhere in the middle, not my final words on this subject. If you

could point me towards a related discussion happening on a blog or public forum

I would be grateful!

No comments:

Post a Comment